When GQ magazine named its list of the "25 coolest athletes of all time", baseball fans undoubtedly observed the dearth of players from the National Pastime. The editors selected San Francisco Giants ace Tim LIncecum, baseball/football star Vincent "Bo" Jackson and St. Louis Cardinals Hall of Famer (HOF) Bob Gibson. If you are under 45 years old or never lived in the Gateway City, you probably thought, Who the hell is Bob Gibson... and why is he one of the '25 coolest athletes of all time"?

When GQ magazine named its list of the "25 coolest athletes of all time", baseball fans undoubtedly observed the dearth of players from the National Pastime. The editors selected San Francisco Giants ace Tim LIncecum, baseball/football star Vincent "Bo" Jackson and St. Louis Cardinals Hall of Famer (HOF) Bob Gibson. If you are under 45 years old or never lived in the Gateway City, you probably thought, Who the hell is Bob Gibson... and why is he one of the '25 coolest athletes of all time"?Granted, Gibson does not seem like an obvious choice - particularly given the more likely omissions: Willie Mays, Derek Jeter, Reggie Jackson, Jim Palmer, Sandy Koufax and, for chrissakes, Mickey Mantle. Credit GQ for recognizing Gibson's tough-as-nails competitive nature that made him one of the most intimidating pitchers in baseball history. In a New York Times magazine article Lincecum mused, "Was Bob GIbson cool? Or was he just a...?" The NYT article did not specify the term, but chances are that it rhymed with "click". And you know that Lincecum was not calling Gibson a rube.

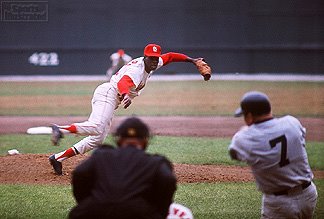

If Gibson were playing today, Lincecum might not have spoken so freely... Gibson would have plunked the Giants ace on principle alone when Lincecum came to the plate. How intimidating was Gibson? HOFer Hank Aaron once said: "Don't dig into Bob Gibson, he'll knock you down. He'd knock down his own grandmother if she dared to challenge him. Don't stare at him, don't smile at him, don't talk to him. He doesn't like it. If you happen to hit a home run against him, don't run too slow, don't run too fast. If you want to celebrate, get into the tunnel first."

It wasn't so much of a method to Gibson's madness but rather his take-no-prisoners approach that drove the Cardinals ace. Born in Omaha, NE in December 1936, Gibson's father for whom he was named - Pack Robert Gibson - died from tuberculosis three months before his namesake entered the world. Gibson's childhood included bouts of rickets and a pulmonary disorder (asthma or pneumonia - the record is unclear). As a high-school student Gibson competed in track, basketball and baseball. Receiving a full athletic scholarship at Creighton University in Omaha, Gibson excelled at basketball - he made third-team, Jesuit All-american during his junior year - and baseball. The Cardinals offered Gibson a $3,000 bonus after he gradated with a degree in sociology. Gibson played with the Harlem Globetrotters for a year. The Cardinals then offered $4,000 if Gibson forsook basketball. Seems like small change by today's standards when one considers that Lincecum received a $2 million signing bonus from the Giants in 2006. But consider also that Gibson in 1958 received more than the national average wage for that year of $3,673.80.

Gibson floated between starting and relieving tasks with the St. Louis organization until manager Johnny Keane took over in 1961. Keane moved Gibson into the Cardinals' starting rotation; the pitcher made the National League (NL) All-Star squad one year later. But Gibson fractured his ankle during the latter part of the 1962 season, and his recovery took half of 1963. The right hander developed a core of two fastballs and a slider. He finished 1963 with a 18-9 record, 3.39 ERA, 204 strikeouts and 14 complete games.

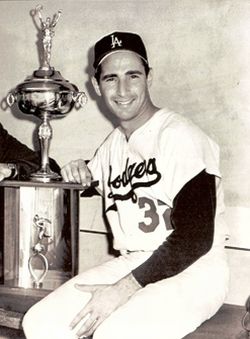

1964 proved a game changer for Gibson and the Cardinals. Four years earlier, the organization - based in a border state with less-than-progressive attitudes - rented a hotel during spring training in Florida where black and white families lived together. The families barbecued meals together, and their kids swam in the motel's pool - a stark contrast to the segregated practices of much of the country. Teammate Bill White - the future president of the National League - and Gibson worked to eradicate the n-word from their teammates' vocabularies. Gibson finished the regular season at 19-12, 245 strikeouts, 17 complete games and 3.01 ERA. He finished 24th in balloting for the Most Valuable Player (MVP) award. The Cardinals won the National League (NL) championship - this in the day before the league championship series and divisional playoffs. Behind Gibson's brilliant pitching - including a win in Game 7 over the New York Yankees - the Cardinals won the World Series. With his 2-1 record, two complete games and 31 strikeouts Gibson was selected as Sport magazine's World Series MVP. Besides the national recognition Gibson received a 1965 Chevrolet Corvette for his endeavors.

Gibson received All-Star berths in 1965 and 1966, but the Cardinals finished, respectively seventh and sixth in the NL standings. In 1967, Gibson pitched the seventh and eighth innings of the MLB All-Star Game. During a game between the Pittsburgh Pirates and Cardinals on July 15, 1967, a line drive off Roberto Clemente's bat struck Gibson's right leg. Being the hard-driven professional that he is, Gibson persevered and pitched to three more batters. Then the right femur above Gibson's ankle snapped. The All-Star pitcher returned to action two months later. The Cardinals won the NL Championships - divisional pennants were two seasons ago - and finished 10½ games ahead of Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, Juan Marichal and the San Francisco Giants.

The Cardinals faced the "Impossible Dream" Boston Red Sox in the 1967 World Series. Gibson yielded only three earned runs and 14 hits while hurling complete contests in Games 1, 4 and 7. Aiding his own cause, Gibson hit a home run in Game 7 in securing a 3-0 victory. The Cardinals won the Series, and Gibson copped his second Corvette as the Series MVP.

Baseball scribes call 1968 "the year of the pitcher." While Denny McLain of the Detroit Lions won 30 games, Meanwhile in the NL, Gibson dominated batters by yielding only 38 earned runs in 304.2 innings for a minuscule 1.12 ERA. Gibson went 22-9 (a record reflected by in efficient run production during his outings), and lead the league with 13 shutouts and 268 strikeouts. Gibson joined an exclusive club of pitchers by winning both the Cy Young Award and the Most Valuable Player (MVP) honors. Gibson received $85,000 in 1968 on the bankroll of the baseball's highest-paid team.

The Cardinals faced the Detroit Tigers in the 1968 World Series. Gibson broke Sandy Koufax's MLB record and fanned 17 Tigers in Game 1; Gibson's record still stands. But defensive gaffes in 1968 cost Gibson and the Cardinals Game 7 and the Series.

The man who received a $4K bonus to sign a MLB contract earned $125,000 in 1969. Gibson compiled a 20-13 record with 269 strikeouts, 28 complete games and 2.18 ERA. The following year, Gibson won his second Cy Young Award with a 23-7 record, 270 strikeouts and a 3.12 ERA (ironically, 2.0 higher than his historic season two years earlier).

Although the Cardinals were no longer contenders, Gibson played until 1975. In his final appearance on the mound, Gibson surrendered a grand slam home run to Chicago Cub Pete LaCock (the son of Hollywood Squares host Peter Marshall). Ever the competitor, Gibson hit LaCock during an oldtimers' game. When sportscaster Bob Costas questioned Gibson about striking a batter, Gibson said blithely, "Robert, the books must be closed."

Gibson's career numbers (251-174, 3,117 strikeouts, 255 complete games, 2.91 ERA) made him an easy first-ballot selection to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1981. At the century's end, The Sporting News ranked Gibson #31 in its list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players. Gibson was also selected to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.

Does a seventysomething Gibson hold his own against the "younger" players? During an old-timers' game in 1993, HOFer Reggie Jackson homered off Gibson during an oldtimers' game. Gibson threw a brushback pitch at Jackson, who didn't get another hit during the contest. Check out the video in which Gibson and Jackson promote their book Sixty Feet, Six Inches. Watch how Gibson takes control of the interview and how Jackson - Mr. October, the man who proclaimed himself as "the straw that stirs the drink" in the Yankee clubhouse - appears soft spoken. Reggie knows better than to upstage Gibson, less he wants a book or a ball buzzing past his ear.